Note: If you're reading this in your inbox, be sure to check out the full post online — it includes great videos you won’t see in the email version!

Shelf Meets Silver Screen Series

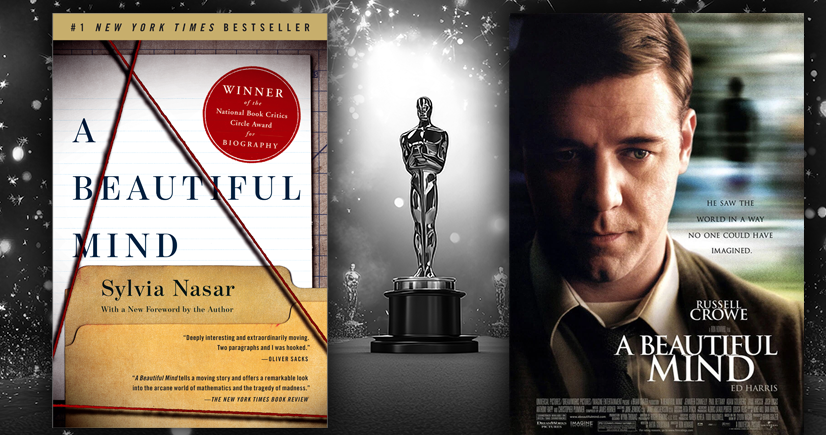

Book Awards:

- 🥇National Book Critics Circle Award Winner Biography/Autobiography 1998

- 🥇Pulitzer Prize Finalist Biography or Autobiography 1999

- 🥇Audie Award Winner Non-Fiction 2003

- 🥇Salon Book Award Nonfiction 1998

- 🥇Writers Guild of America Award Winner Best Adapted Screenplay 2001

- 🥇Golden Globe Award Winner Best Screenplay 2001

Oscar Awards:

- In 1997 Nominated for 8 Academy Awards

- Won:

🏆Best Movie

🏆Best Director: Ron Howard

🏆Best Supporting Actress: Jennifer Connelly

🏆Best Adapted Screenplay: Akiva Goldsman

Sylvia Nasar’s A Beautiful Mind began as a deeply researched biography—a Pulitzer Prize finalist, a National Book Critics Circle Award winner, and an engrossing portrait of mathematical brilliance shadowed by madness. Yet, just a few years later, audiences weren’t just reading about John Nash’s genius; they were feeling it, thanks to Ron Howard’s 2001 film adaptation that swept the Academy Awards.

The Book: An Equation of Genius and Fragility

When Sylvia Nasar published A Beautiful Mind in 1998, she offered readers an insider’s view into the life of a man whose mathematical discoveries reshaped economics but whose mind sometimes betrayed him. Her story was more than a biography—it was an act of empathy. Nasar refused to sensationalize Nash’s schizophrenia; instead, she revealed the human cost and quiet courage behind the math.

Nasar’s focus on the balance between intellectual brilliance and emotional endurance gave the book its gravity. It became essential reading for anyone fascinated by the thin line between genius and instability—themes that resonate now as much as ever with readers who appreciate complex, character-driven nonfiction.

The Adaptation: Hollywood Solving for Heart

Enter Ron Howard, a director known for finding emotional warmth in unlikely places (Apollo 13, Cinderella Man). Working with screenwriter Akiva Goldsman, Howard reimagined Nasar’s intricate biography as something both visually dynamic and emotionally tender. While scholars noted the film simplified Nash’s real experiences, it also translated those abstract internal battles into sensory storytelling—a cinematic formula that made audiences care, not just understand.

Russell Crowe’s restrained, humane portrayal of Nash paired with Jennifer Connelly’s shimmering performance as Alicia turned what could’ve been a cold portrait of intellect into a universal love story. That choice made all the difference. A Beautiful Mind went on to win four Oscars in 2002, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Supporting Actress.

Fact vs. Feeling: The Adaptation Equation

Book lovers often fret about what gets “lost” in the transition to film—the nuance, the inner monologue, and the author’s voice. But in this rare case, the adaptation found a new kind of poetry. Where Nasar’s writing asked us to think, Howard’s film asked us to feel. Together they tell a single, spanning story: one about human complexity, internal struggle, and the mysterious beauty of resilience.

The Stars that Glittered Brightly: Paul Bettany, Ed Harris and Vivien Cardone

The soul of A Beautiful Mind doesn’t just rest in John Nash’s brilliance—it lives in the hauntingly human relationships he builds with people who never existed. Charles, Marcee, and Parcher aren’t just figments of a fractured mind; they are the emotional scaffolding that lets the audience feel what schizophrenia feels like, rather than merely understanding it. Charles (played by Paul Bettany), the charming roommate at Princeton, sweeps into Nash’s lonely world with laughter and easy camaraderie—a balm to an intellect otherwise starving for connection. Through him, viewers see a tender, relatable loneliness healed by friendship’s illusion.

Marcee (played by Vivien Cardone), so small and angelic, deepens that illusion into heartbreak. Her presence—innocent, luminous, and unchanging—perfectly captures the ache of Nash’s delusion: love and warmth rooted in something that can never be real. When Nash later realizes she never ages, the revelation lands like a quiet tragedy. She embodies innocence lost, both his and ours, as we share the painful clarity that imagination has betrayed him.

Then there’s Parcher (played by Ed Harris), the shadow that turns the dream into a nightmare. Ed Harris’s chilling precision gives voice to Nash’s paranoia—the other side of the same coin as Charles’s warmth. While Charles and Marcee represent longing and attachment, Parcher personifies fear and mistrust. Together, these three create an emotional orchestra that guides us through joy, terror, and finally, fragile redemption. Without them, Nash’s battle would be intellectual; with them, it becomes heartbreakingly human. Their presence transforms the film from a biography into an experience of empathy—an invitation to feel the beautiful chaos of a mind at war with itself.

Even years later, for me, Bettany’s performance lingers. He gives shape to the invisible—the longing for connection that defines both genius and madness. Without him, A Beautiful Mind would still be intellectually compelling; with him, it becomes emotionally unforgettable. His portrayal reminds us that the lines between reality and imagination can blur, but what moves us most deeply is never entirely imagined.

Why It Still Matters for Readers with Wrinkles

For mature readers, A Beautiful Mind is more than a time capsule of early-2000s Hollywood or 1990s literary nonfiction. It’s a story about reinvention—both artistic and personal. It reminds us that the mind, no matter how brilliant, is never an island; relationships, compassion, and perseverance form the unsung variables in every equation for survival.

And perhaps that’s the shared DNA between Nasar’s masterpiece and Howard’s Oscar winner: both celebrate the fragile balance between intellect and humanity—the same quality that has us, years later, still turning the pages and pressing “play.”

Even if you are not into non-fiction biographies, you might want to rethink reading or rereading this one. Here is why:

It tells the true story behind the famous film.

The book gives a fuller, more nuanced portrait of John Nash than the movie can manage, including his early life, academic rivalries, and complicated personal relationships that are only hinted at on screen.

It explores what genius really looks like day to day.

Sylvia Nasar traces Nash’s rise as an eccentric young mathematician whose work on game theory reshaped economics and the social sciences, grounding “genius” in classrooms, seminars, and long, lonely problem sets rather than myth.

It shows how one big idea changed how we understand human behavior.

Through Nash’s development of what became known as the Nash equilibrium, readers watch an abstract mathematical concept move from blackboard theory to a tool that now underpins modern economics, political strategy, and negotiations.

It offers a compassionate look at schizophrenia.

The biography does not reduce Nash to his diagnosis; instead, it shows the onset of delusions, the impact of hospitalizations, and the way his illness reshaped his career and family life, all without sensationalizing his condition.

It honors caregivers and the costs of loving someone ill.

Alicia Larde Nash emerges as more than “the wife” in the background; her patience, exhaustion, divorce, and eventual reunion with Nash reveal the quiet, unglamorous work of standing by someone through decades of mental illness.

It invites reflection on marriage, loyalty, and second chances.

For readers who have lived long enough to see relationships bend and nearly break, the long arc of Nash and Alicia’s story—estrangement, slow reconnection, and late-life partnership—will feel especially resonant.

It captures academic life in all its pettiness and glory.

Nasar lets you linger in mid‑century Princeton and MIT, with their brilliant professors, fragile egos, and shifting fashions in theory, offering seasoned readers the pleasure of watching ideas rise and fall over decades.

It corrects the “tortured genius” stereotype.

The book complicates the romantic notion that madness and brilliance are the same thing, showing instead how mental illness disrupted Nash’s work and how his later recovery depended on discipline, support, and time.

It’s a meditation on identity over a lifetime.

Readers watch Nash move from golden boy to campus ghost—the “Phantom of Fine Hall”—and then to Nobel laureate, raising questions about who we are when our careers crumble, our minds betray us, or our reputation changes.

It models a hard‑won, non‑miraculous recovery.

Nash’s gradual remission is depicted not as a sudden cure but as years of consciously “reorganizing” his thinking and slowly re‑entering ordinary life, offering a more realistic and hopeful picture of living with chronic mental illness.

It appeals to readers who enjoy both story and structure.

The narrative moves confidently between intimate biography and the larger history of mathematics and economics, rewarding readers who like their nonfiction layered—with personal drama, intellectual history, and social context intertwined.

It makes an excellent book or film club springboard.

From the ethics of psychiatric treatment to the demands placed on gifted children to what society owes the mentally ill, there is no shortage of meaty questions for a room full of thoughtful, well‑read adults to tackle together.

This movie is so good. Here are a few reasons to watch or rewatch it.

It’s a powerful portrait of mental illness.

The film gives an intimate look at John Nash’s experience with paranoid schizophrenia, from terrifying delusions to the long, uneven work of managing a chronic condition, which can deepen viewers’ empathy and nuance around mental health.

The love story resonates with long-term partners.

Alicia’s steadfast, complicated support—marked by frustration, fear, and loyalty—offers a moving depiction of marriage as something that endures illness, career setbacks, and aging, which may particularly speak to mature viewers who have weathered their own storms.

It explores the link between genius and vulnerability.

By following Nash from a prodigy at Princeton to a Nobel laureate still living with hallucinations, the film challenges romanticized “mad genius” myths and shows brilliance and fragility coexisting in the same life.

It’s grounded in a true, literary-worthy life story.

Adapted from Sylvia Nasar’s biography of John Nash, the movie compresses and reshapes events but still delivers the sweep of a 20th‑century intellectual life—Cold War tensions, academic rivalries, and personal reinvention—that feels as layered as a novel.

The mid-film twist rewards a rewatch.

Once you know which characters and events are hallucinations, a rewatch lets you catch visual and narrative cues you missed the first time, turning familiar scenes into a fascinating exercise in perspective and unreliable reality.

It offers rich themes for book-club-style discussion.

Themes of perception vs. reality, the ethics of treatment, the cost of ambition, and what “recovery” really means invite the same kind of conversation your community has around complex literary fiction.

It treats aging and redemption with grace.

The later sequences, in which an older Nash quietly audits classes and slowly regains respect, portray late-life purpose and dignity in a way that can feel especially validating for viewers in midlife and beyond.

The performances are emotionally layered.

Russell Crowe’s portrayal of Nash captures shifts from brilliance to paranoia to hard-won clarity, while Jennifer Connelly’s Oscar-winning turn as Alicia gives the film its emotional spine and moral center.

It’s a chance to revisit an Oscar-era classic.

With four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Supporting Actress, the film represents a particular moment in early‑2000s cinema that many readers may remember but not have revisited in years.

It opens the door to conversations about treatment and stigma.

The depictions of insulin shock therapy, medication side effects, and the social fallout of Nash’s diagnosis—however dramatized—can spark thoughtful talk about how mental health care has changed and where stigma still lingers.

It pairs beautifully with reading.

For a community of readers, the film can be a springboard to exploring Nash’s biography or books on game theory and mental health, turning movie night into a multi‑text experience much like an extended book club pick.

The 98th Academy Awards (2026 Oscars) will air live on Sunday, March 15, 2026, at 7 p.m. ET (4 p.m. PT). The ceremony will be broadcast from the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on ABC and available to stream on Hulu. Comedian Conan O'Brien is set to host the event.

Comments