Shelf Meets Silver Screen Series

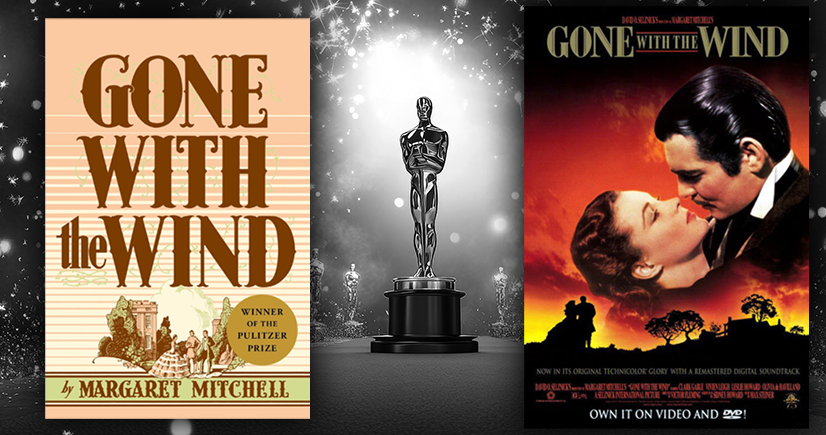

Book Awards:

- 🥇National Book Award Winner – Most Distinguished Novel 1936

- 🥇Pulitzer Prize Winner Novel 1937

Oscar Awards:

- 1939 Nominated for 13 Academy Awards

- Won:

🏆Best Picture

🏆Best Adapted Screenplay - Sidney Howard

🏆Best Director - Victor Fleming

🏆Best Film Editing - Hal C. Kern and James E. Newcom

🏆Best Supporting Actress - Hattie McDaniel

🏆Best Actress - Vivien Leigh

🏆Honorary Award from the Academy

The Book That Broke All the Rules

Margaret Mitchell (1900–1949) was an Atlanta-born journalist who became world-famous for her only published novel, Gone with the Wind (1936). She grew up in a family steeped in Civil War stories, hearing accounts from older relatives that later informed the historical backdrop and Southern perspective of her novel. After a brief but active career as a reporter for the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine, she left journalism in the mid‑1920s following an ankle injury and long convalescence. Bored at home, she began writing the book that became Gone with the Wind, encouraged by her husband John Marsh, and worked on it for years, drafting scenes out of order and storing chapters in envelopes.

When Gone with the Wind hit bookstore shelves in 1936, it wasn’t just a novel — it was an event. Margaret Mitchell’s sweeping Southern saga sold more than a million copies within its first 6 months, captivating Depression-era readers with its unapologetically ambitious heroine, Scarlett O’Hara, and her crumbling world of old Georgia gentry. But what makes Gone with the Wind extraordinary isn’t just its success on paper — it’s how swiftly it leapt from the literary spotlight to cinematic immortality.

By 1937, Mitchell’s debut novel had already won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and broken sales records. Hollywood, always hungry for a sensation, saw the story’s potential. Producer David O. Selznick purchased the film rights for an eye-popping $50,000 — a record-setting sum at the time — and began what would become one of the most storied adaptations in movie history.

A Casting Storm Like No Other

The casting of Scarlett O’Hara might be the most famous game of literary musical chairs in Hollywood history. Producer David O. Selznick auditioned or interviewed well over a thousand actresses and screen-tested dozens, determined to find a “perfect” Scarlett who could sell both the corseted charm and the steel spine underneath. Big names like Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn, Joan Bennett, and Paulette Goddard swirled through the rumor mill, each briefly crowned the “obvious” choice before being nudged aside.

Enter Vivien Leigh, a relatively unknown British actress who arrived on set during the burning of Atlanta sequence and promptly rewrote the narrative. Her tests convinced Selznick and director George Cukor that she had exactly the volatile mix they needed: beauty, “electric” intensity, and that un-teachable air of entitlement that made viewers believe men would orbit her for years. The role won Leigh an Academy Award and permanently fused actor and character in the cultural imagination, a reminder that sometimes the most “impossible to cast” heroine is just waiting in the wings, ready to set the tapestry on fire.

Clark Gable, already dubbed “The King of Hollywood,” was almost too perfect as Rhett Butler — charming, cynical, and impossible to forget.

What often gets lost in the glittering legend is just how chaotic the film’s production was. Gone with the Wind burned through multiple directors, rewrites, and even sets (the now-famous burning of Atlanta scene used the literal destruction of old Hollywood backlots). Selznick was meticulous — some might say maniacal — about staying true to Mitchell’s emotional tone, even as he condensed her 1,000-page novel into a three-hour epic.

The Night Hollywood Stood Still

When the film premiered in 1939, it wasn’t just another movie night. It was a cultural phenomenon. Fans who’d devoured Mitchell’s novel felt they were witnessing their imaginations come alive. Critics hailed it as “the greatest motion picture ever made,” and the Academy agreed: Gone with the Wind swept the 1940 Oscars, winning eight competitive awards, including Best Picture, Best Actress for Vivien Leigh, and a historic Best Supporting Actress win for Hattie McDaniel — the first African American actor to receive an Oscar.

Legacy with Wrinkles

For mature readers who return to both the book and the film today, Gone with the Wind offers a complex tapestry — one woven with grandeur, romance, and controversy. The story’s depiction of race and the Old South no longer reads without discomfort, yet its impact on American popular culture remains undeniable. It stands as a fascinating study in how an era’s dreams and blind spots can be immortalized in fiction and film alike.

I love revisiting classics like this not to freeze them in nostalgia, but to read them with new eyes — eyes that have lived, loved, and learned. Gone with the Wind reminds us how storytelling can define generations, for better or worse, and how the line between page and picture can sometimes vanish in the glow of shared cultural imagination.

Complex, resilient heroine

Scarlett’s arc from pampered teenager to ruthless survivor offers a rich character study in ambition, denial, and willpower that rewards a more mature, second look.

Survival and reinvention under pressure

The novel’s focus on clinging to life, status, and land through war and Reconstruction invites discussion about how people adapt (or refuse to adapt) when their world collapses.

Female agency in a constrained world

Scarlett’s rule‑breaking approach to business, marriage, and propriety highlights early depictions of female independence and its costs inside a rigid patriarchal society.

Epic scope for immersive reading

At over 1,000 pages, the book delivers an old‑fashioned, fully immersive saga—ideal for a slow, communal read that older, experienced readers can savor and dissect together.

Rich themes for layered discussion

Love, obsession, class, land, war, and generational change all intersect, giving your club ample angles for thematic meetings or multi-part discussion guides.

Iconic, flawed romance

Scarlett and Rhett’s volatile relationship, full of power plays and self-deception, is perfect for unpacking what we once labeled “romantic” versus how we read it now.

Interrogating nostalgia and myth

The novel famously romanticizes the “Old South,” making it a powerful text for analyzing how literature creates dangerous myths around slavery, race, and “lost causes.”

Space for anti‑racist critique

Its racist stereotypes and erasures are not a side note but a central reason to reread it critically, using your platform to model how to confront harmful classics rather than ignore them.

Historical context and cultural impact

As a Depression‑era bestseller, a Pulitzer winner, and the basis for one of Hollywood’s most influential films, it lets your readers examine how a single story can shape national memory.

Comparing book and film legacies

Many members know the movie better than the text; rereading the novel invites scene‑by‑scene conversations about adaptation choices, omissions, and shifts in tone.

Ideal for mature, critical readers

Your audience’s life experience positions them to hold the tension between narrative craft and ethical problems, modeling nuanced reading that younger book communities often struggle to sustain.

Gone with the Wind is worth (re)watching for its epic scope, iconic performances, and its usefulness as a conversation starter about storytelling, history, and harmful myths. Here's why.

Scarlett O’Hara as an anti-heroine

A ruthlessly pragmatic, often unlikeable woman at the center of a 1939 film gives you rich material on gender norms, ambition, and survival, especially compared to today’s “unlikable women” in fiction.

The Rhett–Scarlett relationship

Their volatile, often toxic dynamic invites discussion about romanticization of emotional cruelty, consent, and whether the story understands Rhett as a “rogue” or something darker by modern standards.

Survival, resilience, and reinvention

Scarlett’s determination to keep Tara and rebuild after the war foregrounds themes of tenacity, self-interest, and moral compromise that echo many contemporary survival narratives.

A case study in Lost Cause mythology

The film famously romanticizes the antebellum South, glorifies Confederate characters, and erases or distorts the realities of slavery, making it a powerful text for unpacking the Lost Cause narrative and how media shapes memory.

Problematic racial portrayals to interrogate

Stereotyped, subservient Black characters and the suggestion that enslaved people were content with their lot make this essential viewing for understanding Hollywood racism and for modeling how to critically watch beloved “classics.”

Hattie McDaniel’s historic Oscar

McDaniel became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award for her role as Mammy, even as she was segregated at the ceremony, opening discussion about representation, recognition, and the cost of groundbreaking roles.

Film history and box office context

Adjusting for inflation, it remains the highest-grossing film of all time and once topped “greatest movies” lists, which makes it a useful benchmark for how canon formation works and how critical opinion shifts over time.

Technicolor spectacle and production design

Its lavish costumes, sets, and pioneering use of Technicolor, especially in sequences like the burning of Atlanta, show how visual excess can be used to sell an ideology and to overwhelm viewers emotionally.

Adaptation from a controversial novel

Comparing the film to Margaret Mitchell’s novel opens conversations about what Hollywood softened, preserved, or amplified in terms of racism, romance, and politics, and how adaptation choices change a story’s impact.

A touchstone for content warnings and framing

Modern re-releases have come with contextual introductions and debate (for example, removal and restoration on streaming with disclaimers), giving your community a live case study on how to present harmful classics responsibly.

Generational and nostalgia conversations

Many readers’ parents or grandparents saw this as peak romance or prestige cinema, so rewatching now helps unpack how nostalgia can mute critique and how older audiences renegotiate childhood favorites.

Rich pairing options for your club

It pairs well with novels and films that challenge or correct its myths—such as works that center enslaved people’s perspectives or deconstruct the Lost Cause—making it a strong anchor text for themed viewing/reading months.

The 98th Academy Awards (2026 Oscars) will air live on Sunday, March 15, 2026, at 7 p.m. ET (4 p.m. PT). The ceremony will be broadcast from the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on ABC and available to stream on Hulu. Comedian Conan O'Brien is set to host the event.

Comments