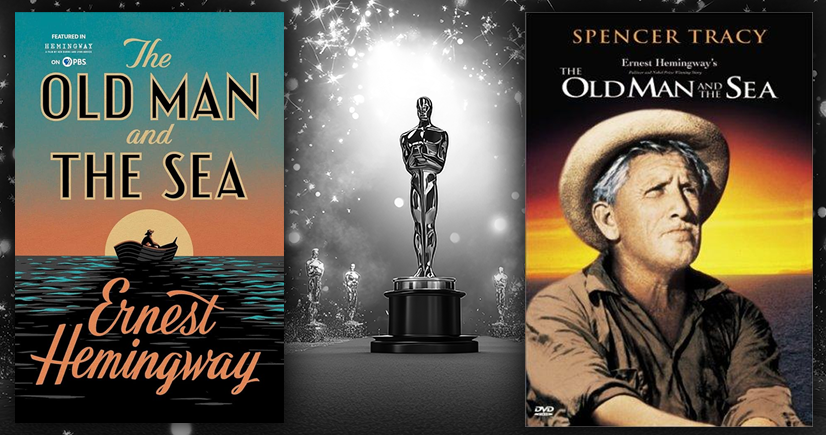

Shelf Meets Silver Screen Series

Book Awards:

- 🥇Pulitzer Prize Winner Fiction 1953

- 🥇Nobel Prize in Literature 1954

Oscar Awards:

- 1939 Nominated for 3 Academy Awards

🏆Best Cinematography - James Wong Howe

🏆Best Musical Score - Dimitri Tiomkin

🏆Best Actor - Spencer Tracy - Won:

🏆Best Musical Score - Dimitri Tiomkin

A Pulitzer Prize and a Career Reborn

Hemingway wrote The Old Man and the Sea late in his career, at a moment when many critics had decided he was washed up, and he knew it. Out of that bruised season came this spare little story about an aging Cuban fisherman who refuses to stop fighting, even when the sea keeps sending him loss.

In the mid‑1930s, Hemingway first sketched the core idea in a brief piece about an old fisherman and a giant marlin, then set it aside while he worked on other books. Years later in Cuba, steeped in his own love of deep‑sea fishing, he returned to the image and wrote the novella quickly, reportedly drafting about a thousand words a day and finishing in roughly six weeks. He drew heavily on his time in Cuban fishing villages and on the Gulf Stream, which is why the details of hooks, lines, currents, and fatigue feel almost documentary.

As for the “why”: on the surface, Hemingway said he wanted the subject and characters to feel absolutely real, not allegorical. But the story’s heartbeat is a quiet argument against surrender—an insistence that a person can be “destroyed but not defeated,” a line many readers have heard as Hemingway talking about his own embattled career and aging body.

When The Old Man and the Sea was published in Life magazine in 1952, over five million copies were sold within two days. Hemingway’s sparse, elemental prose seemed to silence critics who said he was past his prime. The novella earned him the Pulitzer Prize in 1953—and a year later, the Nobel Prize in Literature cited it as a major factor in his win.

But Hollywood had already taken notice.

From Page to Screen: The 1958 Film

In 1958, director John Sturges and actor Spencer Tracy—then one of Hollywood’s most respected stars—brought Santiago’s story to the screen. Filmed partly in Cuba and off the coast of Peru, The Old Man and the Sea blended live action with rare underwater footage. Spencer Tracy’s quiet gravitas made him the perfect Hemingway hero: worn but unbroken, with dignity carved into every weathered line of his face.

The production wasn’t smooth sailing. Sturges left midway, and John Sturges’s vision was later supplemented with sequences by Fred Zinnemann and others. Yet somehow, after all the turbulence, what reached audiences still carried Hemingway’s stripped-down soul.

The Sea, the Struggle, the Award

At the 31st Academy Awards, the film won the Oscar for Best Original Score—composer Dimitri Tiomkin’s soaring, melancholy work capturing both the ocean’s fury and its grace. Spencer Tracy was nominated for Best Actor, and his performance is still hailed as one of the most poignant portrayals of loneliness and endurance in midcentury cinema.

Though critics were divided about how well the novella’s inner simplicity translated to film, audiences felt its pulse. The relationship between a man and his purpose—tested and renewed—resonated far beyond the Cuban coast.

Why It Still Matters

For book lovers, The Old Man and the Sea reminds us of literature’s strange power: a 127-page story about fishing can move mountains within us. And for film lovers, it’s proof that faithful adaptation doesn’t always mean replicating every word. Sometimes, it’s about honoring a heartbeat.

I’ve found that rereading Hemingway later in life, when I’ve endured my own “big fish” battles, brings a newfound tenderness. The sea feels familiar. The struggle feels mine. And maybe that’s what makes both the book and its film timeless companions—for readers and watchers with a few wrinkles of their own.

Rereading The Old Man and the Sea is especially rich for a seasoned, book-club crowd because its apparent simplicity hides a lot of depth that only grows with age and experience. Here are some specific reasons to (re)read it:

It means more when you’re older.

Santiago’s fight against age, bad luck, and a body that no longer cooperates lands very differently when your own joints creak; his stubborn dignity turns into a mirror rather than a metaphor.

The perseverance theme is a gut check.

The novella is essentially one long act of not giving up—Santiago keeps fishing after eighty-four fishless days and refuses to quit on the marlin or the sharks, even when he knows he cannot “win” in any practical sense.

It’s a compact masterclass in style.

Hemingway’s famously spare prose, often described through his iceberg principle, offers clear, simple sentences on the surface with most of the emotional and symbolic weight hidden underneath—perfect for a close read or aloud discussion.

The symbolism rewards a second pass.

On a reread, the marlin, sharks, sea, lions, and even Joe DiMaggio emerge as layered symbols of worthy struggle, loss, hope, faith, and nagging critics, which makes annotation and group conversation unusually rich for such a short book.

It’s a meditation on defeat and dignity.

The book insists there can be honor in losing well: Santiago returns with little more than a skeleton, yet his unbroken resolve reframes the story from “failure” to a kind of quiet, existential victory.

It opens the door to big life questions.

Discussions naturally drift into vocation, calling, what makes a life “successful,” and how to keep purpose when careers, bodies, or roles change—questions that sit right in the wheelhouse of Readers with Wrinkles.

It’s brief but not shallow—ideal for busy readers.

At novella length, it’s manageable for a month when life is full, yet its layers of theme, symbol, and style give you as much to chew on as much longer novels.

It’s a bridge to the rest of Hemingway.

Because it showcases his lean prose, masculine vulnerability, and recurring concerns—courage, pain, and grace under pressure—it works as a gentle reentry point for readers who haven’t touched Hemingway in years (or didn’t love him the first time).

The boy and the old man soften the stoicism.

The relationship between Santiago and Manolin brings in tenderness, care across generations, and hope, which balances the solitary struggle at sea and gives book clubs a human connection thread to follow.

It’s perfect for theme-focused meetings.

You can build a whole evening around perseverance, aging, or “what makes something a worthy struggle,” and the text is strong enough—yet open enough—to keep conversation lively without turning into a homework seminar.

The 1958 film of The Old Man and the Sea is a quiet, enduring classic. It’s short, faithful to the novella, and soaked in themes of aging, endurance, and dignity that land differently when you’ve logged a few decades yourself. Watch or rewatch because:

Spencer Tracy’s “weathered soul” performance is stellar

Spencer Tracy’s turn as Santiago earned an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor, precisely because he wears age, fatigue, and stubborn hope on his face and in his voice. Older viewers will recognize the way he moves—careful, aching, but still fiercely capable—as its own kind of testimony about late‑life courage.

It's a faithful, visual companion to the book

The film closely follows Hemingway’s plot: an old Cuban fisherman, 84 days without a catch, ventures out alone on the 85th day, hooks a massive marlin, and battles it for days before sharks strip the prize to bone. It lets book lovers “re‑walk” the novella’s key beats—Santiago and Manolin, the hooked marlin, the sharks—while seeing how mid‑century Hollywood translated that spare prose into images.

It's a meditation on aging and usefulness

Santiago is mocked in his village, viewed as past his prime, yet he refuses to stop working, learning, and testing himself. For an older audience, his insistence that “a man can be destroyed but not defeated” turns the movie into a gentle argument that worth and vocation don’t have an expiration date.

There are rich book club themes in under 90 minutes

Running about 86 minutes, the film is easy to fit into a club schedule yet packed with discussion fuel: pride vs. humility, defeat vs. spiritual victory, the meaning of success when you come home with only a skeleton. Members can compare how the film handles friendship, faith, and fate—especially the Santiago–Manolin bond—against what they remember or notice in the text.

It is rich with classic studio-era craftsmanship

Shot in the late 1950s and praised for its beauty by outlets like the Los Angeles Times, the movie pairs seascape cinematography with an Oscar‑winning musical score that leans into mood rather than spectacle. For viewers who grew up with studio-era dramas, its pacing, score, and narration feel like stepping back into the cinematic language of their own younger years.

It provides a chance to talk adaptation “wins” and compromises

The production history is famously fraught—multiple directors, location challenges, and visual‑effects experiments to capture that long battle with the marlin. Watching (or rewatching) gives Readers with Wrinkles a case study in what happens when a “simple” book proves surprisingly hard to adapt, and which choices serve Hemingway’s themes versus which feel like 1950s Hollywood fingerprints.

There is deep emotional resonance for those who’ve “been at sea”

Santiago’s loneliness, his conversations with the fish, the sea, and his own memories echo the inner talk many older adults recognize—sorting regrets, victories, and the desire to do “one more big thing.” The final image of the exhausted old man, having lost almost everything yet somehow gained back his quiet sense of self, lands with particular force for viewers who know what it is to fight long, invisible battles.

The 98th Academy Awards (2026 Oscars) will air live on Sunday, March 15, 2026, at 7 p.m. ET (4 p.m. PT). The ceremony will be broadcast from the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on ABC and available to stream on Hulu. Comedian Conan O'Brien is set to host the event.

Comments