The 98th Academy Awards (2026 Oscars) will air live on Sunday, March 15, 2026, at 7 p.m. ET (4 p.m. PT). The ceremony will be broadcast from the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on ABC and available to stream on Hulu. Comedian Conan O'Brien is set to host the event.

You know that quiet satisfaction when a beloved novel gets the movie treatment and it’s actually good? That rare, disbelieving moment when you lean back in your seat, clutch your popcorn, and whisper, “They didn’t ruin it.”

That’s the sweet spot I'm diving into with Readers With Wrinkles’ new blog series—Shelf Meets Silver Screen: The Rare Novels That Ruled Both Publishing and Hollywood.

Over fifteen posts, we’ll celebrate stories that conquered not just bestseller lists but also Oscar night—books that made Hollywood sit up, sharpen its pencils, and say, “We can work with that.”

Frankly, most of us book people are also movie people. We live for both—the quiet rustle of turning pages and the glow of a theater screen. We thrive on characters who breathe twice: once on paper and again in the dark magic of film.

The Miracle of the Double Win

It’s rare for a story to dominate both worlds. Books are sprawling and internal. Movies are visual and compressed. They speak different dialects of the same emotional language. Translating one art form into another without losing its soul? That’s a miracle.

Yet somehow, a select few novels pulled it off—and then won Hollywood’s highest prize. They didn’t just adapt; they ascended.

- Gone With the Wind

- The Old Man and the Sea

- From Here to Eternity

- The Life of Pi

- The Silence of the Lambs

- To Kill a Mockingbird

- The English Patient

- Schindler’s List/Schindler’s Ark

- The Hours

- The Grapes of Wrath

- The Bridge over the River Kwai

- All The King's Men

- American Prometheus/Oppenheimer

- A Beautiful Mind

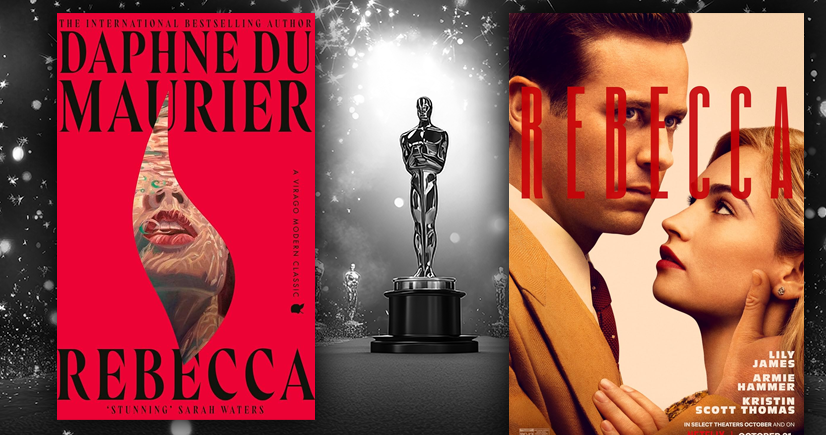

- Rebecca

Each of these stories won Oscars for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor or Actress, and Best Screenplay—or all four. But behind every golden statuette is an even better story: about grit, ego, heartbreak, or sheer dumb luck. About authors who doubted, screenwriters who defied studios, and directors who turned pages into frames.

When a Novel Becomes a New Kind of Legend

Take Gone With the Wind. Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 behemoth wasn’t just a novel; it was a cultural earthquake. She published it, shrugged, and said she hoped to go back to being an ordinary reporter. Instead, she won the Pulitzer, sold millions, and watched her Civil War saga become a film so legendary that even the making of it has its own mythology. Fighting studio heads, rewriting scenes on the fly, Vivien Leigh’s icy brilliance—and that line Rhett Butler delivers that somehow still makes history teachers blush.

Or The Life of Pi. Yann Martel pitched a story that no one wanted: a boy, a tiger, a lifeboat, and a lot of existential philosophy. Turns out, readers wanted exactly that. The book became a phenomenon, then Ang Lee turned it into an oceanic dreamscape that redefined what visual storytelling could do.

It’s as if these novels had some spark baked into their DNA that screenwriters sensed instinctively—an energy that demanded another form.

Why Book and Movie Lovers Speak the Same Language

Some readers proudly wave a “the book was better” flag—and sure, sometimes it is. But most of us secretly adore both versions, because we experience stories the way music lovers experience live concerts and vinyl: each scratches a different itch.

There’s a deeper reason for the overlap. Stories that win both major literary prizes and Oscars usually explore universal humanity. They’re not trendy or gimmicky. They’re about the stuff that never stops mattering—freedom, love, morality, injustice, hope.

When storytelling hits that primal nerve, it transcends the medium. As readers, we recognize it instantly. As moviegoers, we crave seeing it anew.

And let’s face it—sometimes seeing Atticus Finch or Oskar Schindler embodied on screen transforms what we thought we knew about courage.

The Craft Behind the Glory

What fascinates me most is that the novelist and the filmmaker are always working toward the same impossible goal: to make you feel something true.

Ernest Hemingway stripped his prose bare in The Old Man and the Sea, delivering loneliness and grit with surgical precision. When John Sturges adapted it for film, he couldn’t rely on Hemingway’s internal monologue. So, he leaned on color, pacing, and silence—a cinematic version of Hemingway’s sentences.

That’s the thread we’ll follow in this series: why these fifteen novels—out of the millions written—made that rare leap from beloved book to Oscar darling.

When the Silver Screen Adds Something New

A great adaptation doesn’t replace the original; it expands it. Think about Schindler’s Ark. Thomas Keneally’s book is meticulously reported, a document of moral awakening. But Spielberg’s film turned those facts into a haunting visual elegy. Black-and-white frames with a single red coat. A factory as sanctuary. Music that still echoes decades later.

The movie didn’t just “adapt” the book—it gave history a pulse.

Likewise, To Kill a Mockingbird’s leap from Harper Lee’s remarkable prose to Gregory Peck’s embodiment of Atticus Finch wasn’t just translation—it was consecration. The film helped cement the book’s place in every classroom and conscience across generations.

That’s what this series is about: those rare, electric moments when art evolves.

On Hope, Oscars, and Hamnet

This year's Oscar presentation is about six weeks out (March 15th), so there is plenty of time to jump into each of these book-to-movie masterpieces. But I’d be remiss not to mention one hopeful on the horizon: Hamnet. Maggie O’Farrell’s aching, luminous novel about Shakespeare’s family has all the makings of an award magnet. The Golden Globe people thought so. It’s literary yet intimate, bursting with grief and love—the very qualities that often touch both readers and Academy voters right where it counts.

If Hamnet makes it to Oscar gold, it’ll be a modern miracle—a reminder that storytelling’s power to bridge time and art forms is still alive and well.

When the Curtain Falls… and the Lights Come Up

So, as Shelf Meets Silver Screen kicks off, here’s my invitation: grab your favorite reading chair and your best popcorn bowl. Over the next few weeks, we’ll walk the red carpet of stories that proved words can become light, ink can become performance, and that sometimes, the book and the movie are part of the same heartbeat.

Because in the end, whether you’re flipping pages or sitting in the dark, the goal is the same: to be moved—to see yourself, your heartbreaks, your hopes—reflected back through art.

After all, the shelf and the screen have always been two sides of the same story.

Comments