Shelf Meets Silver Screen Series

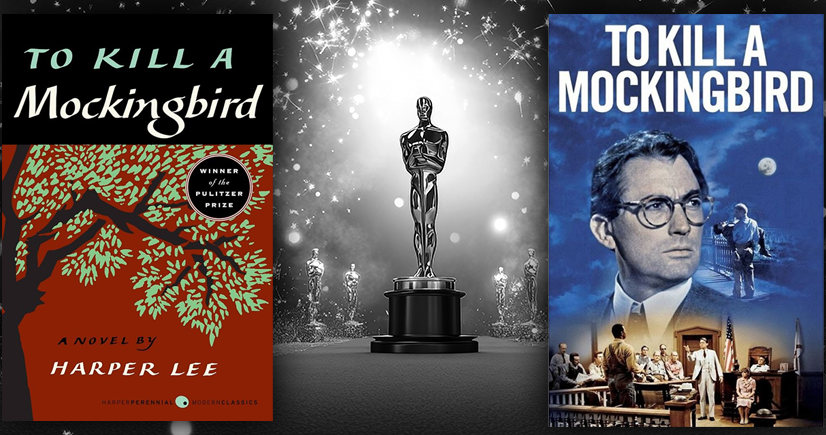

Book Awards:

- 🥇Pulitzer Prize Winner Fiction 1961

- 🥇National Book Award Finalist Fiction 1961

- 🥇Audie Award Winner Classics 2007

- 🥇Alabama Author Award Fiction 1961

- 🥇Cheltenham Prize for Literature 1960, 2010

Oscar Awards:

- 2013 Nominated for 8 Academy Awards

- Won:

🏆Best Actor—Gregory Peck

🏆Best Adapted Screenplay—Horton Foote

🏆 Best Art Direction (Black-and-White)—Alexander Golitzen, Henry Bumstead, and Oliver Emert

Just so you know, To Kill a Mockingbird is my favorite book of all time. You've been warned in case you wonder about all the "gushing" below.

Some stories stay with us, not just because they’re beautifully written, but because they remind us who we are—or who we ought to be. Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is one of those rare few. Published in 1960, it won the Pulitzer Prize just a year later and quickly became an American classic. Then in 1962, it made another leap—from the quiet streets of Maycomb, Alabama, onto the big screen—and straight into Oscar history.

The Book that Stopped People in Their Tracks

When To Kill a Mockingbird first appeared, readers were struck by its moral gravity wrapped in the innocence of a child’s voice. Through Scout Finch’s eyes, Harper Lee confronted the ugliness of prejudice, the courage of decency, and the tenderness of family. For many of us, it was the first time we saw justice and conscience take center stage in a story that felt so small-town and yet so universal.

That duality—the sense of both intimacy and magnitude—made the novel ripe for adaptation. But Hollywood, famously risk-averse with literary works, needed the right ingredients: a visionary director, a trustworthy script, and the perfect Atticus Finch.

The Hollywood Treatment—Without Losing Its Soul

Director Robert Mulligan and screenwriter Horton Foote pulled off something rare: a literary adaptation that felt as sacred as its source. Foote’s screenplay honored Lee’s dialogue without drowning in it, capturing the atmosphere of Southern stillness with a sense of moral urgency.

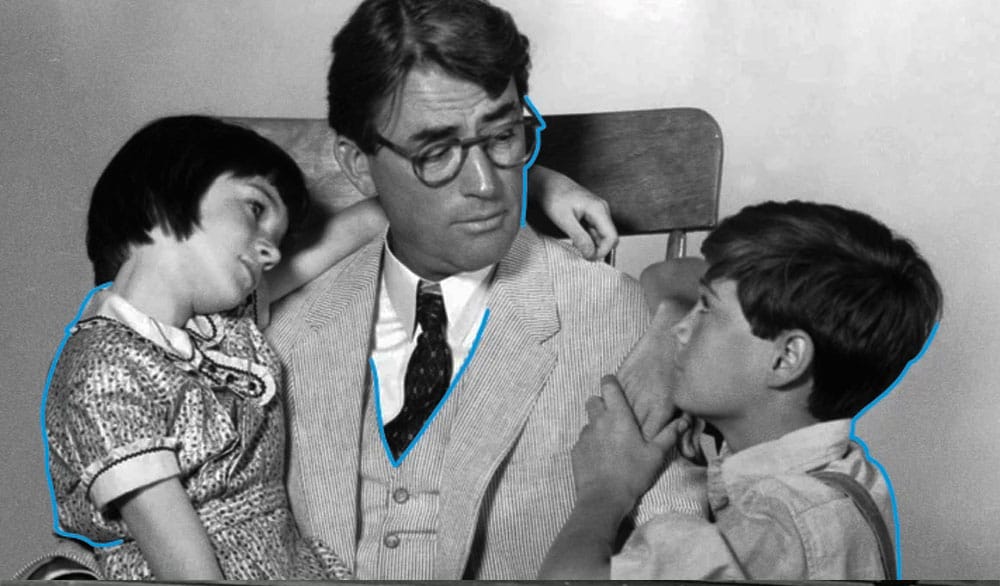

Then came Gregory Peck. His Atticus Finch wasn’t just a performance; it became a template for decency itself. Peck approached the role with a quiet authority that mirrored how readers imagined Atticus—neither saint nor savior, just a man doing what’s right when it’s terribly hard.

When the film was released in 1962, it was both a critical and cultural event. The black-and-white cinematography lent Maycomb a timeless quality, and Elmer Bernstein’s score a subtle ache. Viewers recognized the same courage and conscience that had moved them on the page.

From Pulitzer to Oscar Gold

The film earned eight Academy Award nominations and took home three: Best Actor for Gregory Peck, Best Adapted Screenplay for Horton Foote, and Best Art Direction. It also earned something less tangible—the respect of readers who feared Hollywood might ruin their beloved novel. Instead, To Kill a Mockingbird became the rare story cherished equally by book lovers and moviegoers alike.

Why It Still Matters to Readers (and Viewers) with Wrinkles

For those of us who return to To Kill a Mockingbird after decades of life lived, it reads differently now. Scout’s innocence feels more fragile; Atticus’s quiet bravery, more necessary. Watching the film again reminds us how powerfully compassion translates between mediums—whether you’re turning pages or watching shadows flicker on a screen.

We often talk about the divide between “book people” and “movie people,” but Mockingbird is the bridge between both. It proved that when a story is rooted in truth, it can win every kind of prize—from Pulitzers to Oscars—and, most importantly, the hearts of generations of readers who still believe in the good.

If you've never read To Kill a Mockingbird, stop what you are doing and get the to your computer, or better yet, to a bookstore, buy the book and READ IT. If you already read it once or twice, or ten times like me, rereading as an older, more seasoned reader reveals layers of moral complexity, grief, and compromise that may have gone unnoticed in a first teen reading, especially around Atticus, Mayella, and the townspeople. Here are a few reasons to bury yourself in this classic.

The themes are painfully current.

The novel’s exploration of racism, prejudice, and a biased justice system mirrors ongoing debates about inequality and civil rights, making it feel eerily “of today” rather than a relic of the 1930s.

It deepens our understanding of empathy.

Scout’s journey from fear to compassion—especially in how she comes to “stand in Boo Radley’s shoes”—invites readers to reexamine who they other, misunderstand, or overlook in their own lives.

Courage looks different when you’re older.

Atticus’s quiet, steady bravery, Mrs. Dubose’s painful fight against addiction, and even Scout’s small acts of standing up become richer, more challenging portraits of what moral courage costs in real life.

It’s a powerful reflection on parenting and influence.

For readers who are parents, grandparents, or mentors, Atticus’s choices—what he explains, what he shields, and how he models integrity—offer a nuanced look at raising children in an unjust world.

The coming-of-age story hits closer to home.

Seen through adult eyes, Scout’s loss of innocence and gradual moral awakening highlight our own journeys from naïve certainty to a more complicated, but more compassionate, understanding of people.

It challenges our ideas about justice versus mercy.

The way the community treats Tom Robinson and the later decision to protect Boo Radley forces readers to wrestle with when the law serves justice—and when mercy may be the truer justice.

Boo Radley means more the second (or tenth) time.

On reread, Boo shifts from spooky neighborhood legend to a symbol of how societies scapegoat and erase “outsiders,” raising questions about who we choose not to see in our own communities.

The language and storytelling are a pleasure to savor.

Lee’s mix of humor, childlike observation, and lyrical description offers the kind of rich, old-fashioned prose that rewards slow reading, underlining, and reading aloud.

It reconnects us with a shared cultural touchstone.

Because the book is so widely taught and discussed, revisiting it helps readers join contemporary conversations about its strengths, blind spots, and ongoing impact on how we talk about race and morality.

It sparks reflection on who we’ve become.

Returning to Maycomb after years away invites readers to notice how their reactions have changed—who they sympathize with, what outrages them now, and how their own moral compass has evolved over time.

The movie is as good as the book. Here is why:

It brings the novel’s themes to life

The film translates the book’s exploration of racism, injustice, and moral courage into unforgettable images and performances, making the story’s ethical questions feel immediate and emotionally urgent.

Gregory Peck’s iconic Atticus Finch

Gregory Peck’s portrayal of Atticus Finch won the Academy Award for Best Actor and is widely ranked among the greatest screen performances and movie heroes of all time, offering a nuanced model of integrity and quiet bravery.

A masterclass in restrained, classic filmmaking

Shot in black and white with careful, character-focused direction, the movie uses silence, shadows, and close-ups to build tension and empathy rather than relying on spectacle, which rewards attentive, mature viewers.

Powerful courtroom drama sequences

The trial of Tom Robinson is considered one of cinema’s finest courtroom set pieces, combining sharp dialogue, moral complexity, and simmering tension that invite viewers to confront systemic racism and bias.

A rich coming-of-age perspective

Told through Scout’s eyes, the film captures the confusion and wonder of childhood while gradually exposing her to the realities of prejudice and courage, which resonates deeply with adults reflecting on their own moral formation.

Nuanced portrayal of empathy and “walking in someone else’s shoes”

Moments like Scout standing on Boo Radley’s porch, imagining the world from his perspective, visually embody the story’s central lesson about seeing others with compassion.

Award-winning, literary-grade screenplay

Horton Foote’s adaptation won the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay and is consistently listed among the greatest screenplays ever written, preserving the novel’s spirit while crafting a tight, cinematic narrative.

Memorable supporting performances

Mary Badham as Scout and Brock Peters as Tom Robinson give performances that feel startlingly natural and emotionally raw, adding depth and humanity to the film’s exploration of innocence and injustice.

Robert Duvall's film debut

In his hauntingly quiet film debut, Robert Duvall steps from the shadows as Boo Radley—a ghostlike figure whose single, wordless appearance says more about kindness, fear, and misunderstanding than pages of dialogue ever could. Unbelievable

The 98th Academy Awards (2026 Oscars) will air live on Sunday, March 15, 2026, at 7 p.m. ET (4 p.m. PT). The ceremony will be broadcast from the Dolby Theatre in Hollywood on ABC and available to stream on Hulu. Comedian Conan O'Brien is set to host the event.

Comments